This article introduces a new mechanism for preventing bad actors from abusing privacy systems based on shielded pools. The goal is to present the idea to the broader Ethereum community and get feedback on the following aspects:

- technical feasibility,

- alignment with values shared by the Ethereum community,

- potential for enabling broader adoption of privacy solutions based on shielded pools.

After a short introduction and explanation of the problem, we present an idealized version of the proposed system to show the idea in the simplest possible form. Then we discuss, in technical terms, possible practical instantiations of the system and analyze the resulting trade-offs and deviations from the idealized version, after which we compare it to Proofs of Innocence (the current state-of-the-art solution).

Preliminaries

The idea of shielding assets is almost a decade old and was first popularized and brought to production by ZCash. Since then, many similar protocols have been built and deployed as smart contracts on Ethereum and other EVM chains. These include TornadoCash, Railgun, Privacy Pools, and Blanksquare, and these are our main focus in this write-up (we will call them shielded pools). For the sake of this article, we employ the following, maximally simplified model of these protocols (following TornadoCash): there are two operations, deposit and withdraw:

deposit— the user deposits1 ETHin the contract, and a hashed “note” with1 ETHand the user’s “spend key” is added to a Merkle tree in the contract,withdraw— the user withdraws1 ETHthat they have previously deposited viadeposit. The corresponding note is spent by revealing the so-called “nullifier”.

For technical details, we refer to the TornadoCash Whitepaper, the ZeroCash Paper, or any recent exposition. The main idea is that the withdraw operation cannot be linked to any particular deposit operation, and hence all the user’s ETH mixes with each other. We note that many protocols now allow different deposit and withdrawal amounts, splitting notes into multiple withdrawals, using ERC20 tokens, etc. — these modifications can be made, and all the ideas in this article are still relevant for more general protocols. Similarly, some shielded pools allow shielded-to-shielded transfers; this feature can also be supported with the system proposed in this article, but for the sake of simplicity we do not discuss it.

An important consideration when deploying blockchain privacy systems is the issue of misuse by bad actors. A typical example is black hats stealing tokens from contracts on-chain and then using shielded pools to launder those funds (making them hard to track by law enforcement). The ethical and regulatory considerations around this problem have been widely discussed and are out of scope for this article. We focus on the technical aspects. The reference solution we are comparing against is Proofs of Innocence (see, e.g., this paper by Buterin et al.). Below is a rough summary of what it does (currently implemented in Privacy Pools):

- When making a deposit, the

deposit_identers a queue maintained by an off-chaincompliance_system. - The

compliance_systemspends a certain amount of time (realistically between 1 hour and 7 days) verifying that the deposit is not illicit. If the deposit is confirmed to be clean, this information is posted on-chain by thecompliance_system, and thedeposit_idis added to a Merkle tree allowlist (needed for technical reasons). - The user has two ways to perform

withdraw:- Regular: possible only when

deposit_idis on the allowlist. The user can then withdraw privately. - Ragequit: always possible. The user can withdraw, but must publish the

deposit_idalong with the transaction, which makes it linkable with the deposit and therefore not private.

- Regular: possible only when

- The

compliance_systemcan add new entries to the allowlist and also remove them (at least in the case of Privacy Pools).

In short, the PoI (Proofs of Innocence) system protects the shielded pool from illicit deposits by rejecting funds that are illicit or suspicious based on public information (tracking the funds on-chain).

Idealized Retroactive Anonymity Control System

We propose a system alternative to Proofs of Innocence called Retroactive Anonymity Control (RAC for short). In this section, we introduce an idealized version of the protocol, meaning one that assumes perfect cryptography exists for the purpose of implementing RAC. We use this approach to focus on the fundamental properties of the system rather than implementation details. Later in the article, we provide three concrete ways to implement RAC and discuss the resulting trade-offs.

For RAC, we make the following adjustments to the normal shielded pool operations:

- For each

depositoperation, the user generates a newview_key(think: 256 bits). - To both

depositandwithdraw, the user attachesMAC(view_key)— a kind of “signature” that allows authentication of the signer, but only when the key is known. Concretely, thinkMAC(view_key) = (salt, hash(view_key, salt)). - The protocol forces the user to use the same

view_keyfor bothdepositandwithdraw, for example by savingview_keyin the note. However,MAC(view_key)is randomized, so external parties cannot link thedepositto thewithdrawwithout theview_key.

Let’s analyze what we have gained:

- Each

(deposit, withdrawal)pair has a unique (and enforceable)view_key. - Given the

view_keyof a deposit (or withdrawal), anyone can link (and therefore deanonymize) a particular transfer through a shielded pool. - By default, the user generates the

view_keyand keeps it only for themselves, which makes the attachedMACs just random noise.

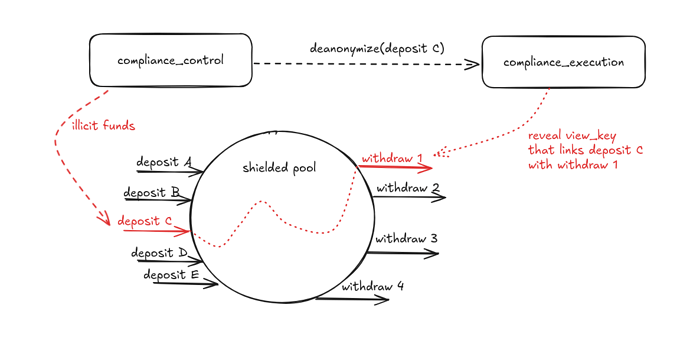

The RAC system consists of the following components:

compliance_control— an Ethereum address of the entity making decisions about potential deanonymization of transfers via the shielded pool.compliance_execution— an Ethereum smart contract in charge of revealing theview_keyrequested bycompliance_control. It will typically rely on some off-chain activity.

Here is how a shielded pool with RAC works:

- Users can always

depositandwithdrawwith no limitations. There are no allowlists and no waiting periods. - If at any time a

deposit(orwithdraw) is detected to come from illicit sources andcompliance_controldecides that the underlying funds should not benefit from anonymity, thencompliance_controlmakes adeanonymize(...)call to thecompliance_executioncontract, with inputs pointing to a particulardepositorwithdraw. - Upon receiving a

deanonymize(...)call, thecompliance_executioncontract asynchronously and publicly outputs theview_keyof the requesteddepositorwithdraw. This allows anyone to link the correspondingdepositandwithdraw, effectively removing this transfer from the anonymity set.

A few comments are in order:

- The cryptographic magic, obviously, happens in

compliance_execution, and we explain how this can be done in a later section. For now, let’s assume this is possible. compliance_controlis the only party that can invoke deanonymization viacompliance_execution— therefore, we expect that it is not a single centralized actor, but a DAO or a multi-member “compliance council.” The details of how to instantiate this entity are out of scope for this article.- Note that we do not have to trust the output of

compliance_execution, because the correctness ofview_keycan be verified againstMAC(view_key)(this is the crucial property of the MAC).

Short summary: in RAC, users can always freely deposit and withdraw, but there is an on-chain entity (a DAO, or similar) called compliance_control that can, at any moment, retroactively deanonymize any (deposit, withdraw) pair. This happens transparently through an on-chain request, and the resulting view_key is also posted on-chain for everyone to see.

Concrete Instantiations

The previous section describes the idealized protocol but does not explain how to instantiate compliance_execution. We now discuss three ways of achieving this using three different cryptographic techniques. We present them in order from most practical (and easiest to implement) to least practical (hardest to implement).

Instantiation 1: TEE network

We assume that there exists a key pair (sk, pk) for asymmetric, SNARK-friendly encryption (ElGamal in a suitable group can be used) and that, in addition to MAC(view_key), the user also publishes Enc_pk(view_key) in each transaction (both deposit and withdraw). In other words, the user encrypts their view_key in every transaction with the key pk, and only the party holding sk (the TEE) can decrypt it.

The idea is simple. We instantiate a set of TEEs, operated by various independent parties. Ideally, running a copy of the TEE should be permissionless, but in light of recent attacks this is tricky, though not fundamentally impossible. Each TEE holds a copy of the sk key. The key generation protocol and distribution of the key among TEEs is not entirely trivial engineering-wise, but it is well understood and already standard practice for TEEs. Each TEE runs a program that roughly does the following:

- To instantiate your

sk, copy it from another TEE running the same program (details omitted). - If you hold your

sk, never leak it in plaintext. If another TEE running the same program requestssk, provide it through an encrypted channel (details omitted). - Upon a

deanonymize(finality_proof, args)request, perform:- Run an Ethereum light client to verify that

finality_proofis a correct finality proof of adeanonymize(args)call to thecompliance_executioncontract on Ethereum. - Recover

Enc_pk(view_key)fromargsand decrypt it usingskto learnview_key. - Output

view_keyin plaintext.

- Run an Ethereum light client to verify that

In practice, this means that whenever compliance_control requests deanonymization of a particular deposit or withdrawal, any TEE operator can call their “magic box” to retrieve the view_key (they only need to provide a valid finality proof so that the TEE knows the request truly occurred on Ethereum). The operator then submits view_key on-chain (and the contract can verify correctness).

The resulting security guarantees are:

- As long as there is at least one honest operator, the protocol is live — that is, deanonymization requests by

compliance_controlwill be answered. - Even if all operators are dishonest, as long as the TEEs themselves are not compromised, the anonymity of the protocol is preserved.

- If, for some reason, all copies of the TEE crash at the same time and all copies of

skare lost, then the protocol can no longer perform deanonymization. - If any TEE is compromised and its operator recovers

sk, then this operator can secretly deanonymize all users (past, present, and future). The impact of this could be reduced by periodically rotatingsk.

Instantiation 2: MPC committee

Similar to the first instantiation with TEEs, we assume a key pair (sk, pk) and a fixed N-node committee that (1) generates (sk, pk) using DKG, and (2) serves deanonymization requests from the chain using a t-of-N threshold decryption protocol. This could be implemented using an existing solution such as Shutter.

Depending on the exact details of the decryption protocol, the security properties differ slightly, but roughly we get:

- As long as enough committee nodes behave honestly (and do not lose their key shares), the protocol is live.

- Unless a large portion of the nodes collude and recover the key

sk, the anonymity of the protocol is preserved. Otherwise, the colluding nodes can deanonymize all users (past, present, and future).

Instantiation 3: Witness Encryption

This instantiation is still in science-fiction territory, but since WE is being actively researched, it may become viable in the future.

The idea here is that there is no “master key” anymore. Instead, the user attaches a witness-encrypted view_key to each of their transactions, where the witness is the following piece of data:

- An Ethereum finality certificate (think of the data used by a stateless light client) for a contract call to the

compliance_executioncontract bycompliance_control, demanding deanonymization of the transaction being sent by the user.

This may sound confusing to readers unfamiliar with witness encryption, but the main idea is that in witness encryption, any efficiently verifiable piece of data can serve as a decryption key. In our setting, we want to decrypt only if compliance_control makes a deanonymization request, so the “key” must be a proof that such a request has taken place.

Comparison to Proofs of Innocence

When comparing to PoI, we consider Instantiations 1 and 2, because the third one is not yet practical.

Efficacy in Countering Bad Actors

Since the RAC mechanism is retroactive and deanonymization can be ordered at any time, it is more effective than PoI. One case where RAC would work and PoI would not is when an actor enters with illicit funds, but their illicitness becomes apparent long after the deposit (later than the verification window). At that point, the funds have likely already been withdrawn, so even removing the deposit_id from the allowlist does not help. RAC, however, can still deanonymize the transfer. A good example here is this exploit of the Mirror protocol, which went unnoticed for seven months.

Complexity and Robustness

The RAC system is significantly more complex and thus more likely to have bugs or be vulnerable to attacks on multiple layers (depending on whether TEE or MPC is used). Moreover, the liveness of the protocol (the ability to process deanonymization requests) is harder to preserve in practice (key loss, crashes of all TEEs, etc.). For these reasons, RAC can be considered less robust.

Entering Barrier

Since compliance_control in RAC is retroactive, it can be much more lenient than the compliance_system in PoI. There are several reasons for this:

- PoI must make decisions quickly because the user is literally waiting for approval; in uncertain cases, it is safer to reject a deposit.

- PoI should not allow — or must be extremely careful about — looping, i.e., a situation where the user withdraws and then deposits again. RAC allows this, and as explained below (Composability), this behavior is natural for certain applications.

- PoI may need to reject deposits from lesser-known CEXes or generally less trusted centralized parties, whereas RAC can accept deposits and only deanonymize later if there are claims about specific deposits.

Security and Trust Assumptions

No matter whether we use TEEs or MPC to instantiate RAC, there are new assumptions required to preserve anonymity in the system.

In PoI, once the user withdraws from the shielded pool, they are guaranteed they cannot be deanonymized anymore (even if their deposit entry is later removed from the allowlist). In RAC, there is no such guarantee, and users may worry: “What if, in the future, my private records leak due to an exploit?” These concerns can be partially mitigated (see Remarks section) but never fully eliminated.

Composability

Being composable with existing public DeFi protocols is an important factor for the adoption of shielded pools. A typical flow may look like:

withdrawtokens A from a shielded pool,swaptokens A for tokens B on Uniswap,deposittokens B back into a shielded pool.

This pattern is an example of “looping” (withdrawing and depositing the same funds), and might be an attempt by a bad actor to reset the deposit_id to a fresh one. Allowing such a deposit in PoI is questionable, because removing entries from the allowlist becomes far less effective.

RAC does not suffer from this issue, and is therefore arguably more composable.

Remarks

- One important concern about RAC as described above is that deanonymization requests can be executed on arbitrarily old user interactions, so the user never gets a guarantee that their historical records are forgotten for good. This can be addressed by introducing a deanonymization horizon — for example, activity older than one year cannot ever be deanonymized. This can be achieved in Instantiations 1 and 2 by rotating the

(pk, sk)key pair every year (the TEE can be programmed to forget the key, and the MPC committee can rerun the setup). - One possible practical attack a black hat could attempt against RAC is aggressive looping. For example, assume a black hat holds 1M USDT, and performs

deposit → withdraw1,000 times in a row with the same funds. To unwind the trace, thecompliance_controlentity would need to perform 1,000 sequential deanonymization requests, which could be time-consuming and problematic operationally. Mitigations include:- Fees: if the shielded pool charges a percentage fee on deposit or withdrawal (as state-of-the-art solutions do), then aggressive looping of large amounts becomes very costly for the attacker.

- Minimum deposit amounts: a more malicious version of the attack would be to split 1M into many small deposits and loop them individually. This becomes less problematic if there are reasonable minimum deposit limits.

Conclusion

We introduced a new idea for securing shielded pools against bad actors via retroactive deanonymization controlled by an on-chain compliance_control address. The comparison with PoI is certainly not exhaustive, and there are many aspects of RAC that could be improved. We therefore ask for feedback on this idea — please leave comments, technical or otherwise; all are valuable to us.

The Blanksquare Team.