In this post we discuss problems with the current draft spec for ERC-7683 and introduce a redesign meant to address them, as a result of collaboration between intent protocol implementers including Across and Uniswap (original ERC authors), LI.FI, and OpenZeppelin, in the context of the Open Intents Framework.

Thanks to Alexander Lindgren, Mark Gretzke, Chris Cashwell, Pepe Blasco, Matt Rice, Barnabé Monnot, and Orca for feedback and review.

tl;dr

- ERC-7683 aims to enable interoperability of fillers across intent protocols. As drafted, it doesn’t deliver on this due to non-standard

orderData, conservative profit estimations, little room for protocol variability, and gas overhead. - We propose an ERC redesign focused on standardizing resolvers: contracts tasked with translating protocol payloads into a common language of filler instructions. This enables programmable fillers that can adapt and participate in any intent protocol given a resolver for it.

- A common language of resolved orders can be built out of general purpose building blocks.

Motivation

Contributors to the Open Intents Framework have been building primitives for intent protocols and for the different sides of the intent marketplace. OIF Contracts is a modular intent protocol, and the OIF APIs can provide interoperability on the demand side. Interoperability on the supply side, however, is still lacking. That is the role of ERC-7683, which despite significant interest across the ecosystem hasn’t gained much adoption. We analyze design issues that could be limiting it and propose an improved approach to the standardization of intent protocols for filler interoperability.

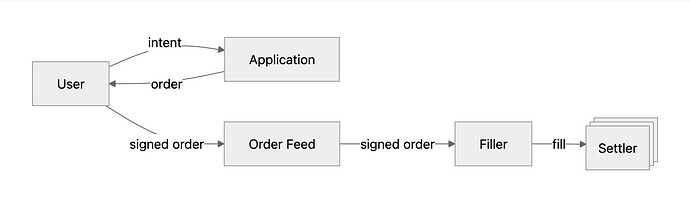

Order Lifecycle

We model the lifecycle of an order through an intent protocol as follows:

- A user expresses an intent to an application.

- The application synthesizes an order that implements the user intent in a protocol.

- The order is signed by the user to authorize the required funds.

- The signed order is submitted to an order feed, on or off chain.

- A network of fillers subscribed to the feed evaluates the safety and profitability of the order.

- A filler delivers the order to the protocol’s settlement contracts for execution with its own liquidity.

- Settlement of the order proceeds and the filler is compensated.

The scope of ERC-7683 as currently drafted extends over most of this lifecycle:

- How orders are encoded (

OnchainCrossChainOrderandGaslessCrossChainOrder) - How orders are published and subscribed to via an onchain feed (

IOriginSettler.open) - How the filler escrows funds if an offchain order feed is used (

IOriginSettler.openFor) - How the filler learns implementation-agnostic information about orders (

ResolvedCrossChainOrder) - How the filler executes the fill (

IDestinationSettler.fill)

The broad goal behind this standardization effort is to make intent protocols interoperable, meaning that the different actors and steps along the way can proceed in a protocol-agnostic way. However, we believe this version of ERC-7683 doesn’t achieve this goal in practice.

Problem #1: Implementation-specific order data

Although the ERC defines standard data types for orders, these types are parameterized by implementation-specific fields. Indeed, this is where many key order parameters are meant to be included:

/// @dev Arbitrary implementation-specific data. Can be used to define tokens,

/// amounts, destination chains, fees, settlement parameters, or any other

/// order-type specific information

bytes orderData;

/// @dev Type identifier for the order data. This is an EIP-712 typehash.

bytes32 orderDataType;

Because of this field, orders are only superficially standardized. A filler that intends to fill “ERC-7683 orders” must actually implement support for different protocols’ subtypes, which is not meaningfully different from a situation where each protocol implements an entirely custom interface.

Similarly, users or applications that originate orders must choose a specific subtype of order data to include in their order, so the extent of standardization is very limited on this end of the lifecycle as well.

While it is possible for implementations to share a set of standard subtypes, we believe this is not realistic, as differences in order parameters tend to be necessary for protocols to innovate and differentiate themselves.

Problem #2: Profits can only be approximated

To make up for the fact that an order’s tokens and exact amounts are included in the implementation-specific part of an order, the ERC defines resolve functions and a ResolvedCrossChainOrder type. This functionality can be used by fillers to learn details about a concrete order in a fully standardized and implementation-agnostic way.

Among the fields of resolved orders are maxSpent and minReceived (to be interpreted from the filler’s perspective):

/// @dev The max outputs that the filler will send. It's possible the actual

/// amount depends on the state of the destination chain (destination dutch

/// auction, for instance), so these outputs should be considered a cap on

/// filler liabilities.

Output[] maxSpent;

/// @dev The minimum outputs that must be given to the filler as part of order

/// settlement. Similar to maxSpent, it's possible that special order types may

/// not be able to guarantee the exact amount at open time, so this should

/// be considered a floor on filler receipts. Setting the `recipient` of an

/// `Output` to address(0) indicates that the filler is not known when

/// creating this order.

Output[] minReceived;

The goal is for the filler to be able to compute whether an order is profitable to decide whether to take it. However, note that this only provides a lower bound on profit. While this provides safety, if the bound is not tight it can result in orders incorrectly appearing unprofitable and not getting filled.

In the worst case, protocols are not able to provide a maxSpent other than UINT256_MAX (a trivial bound). Often this is simply because the order signed by the user binds the worst price they are willing to accept, which is the opposite of the bounds above. In other cases, it is because the bounds are static, in particular they cannot reflect when a filler is able to bid on the price they’re willing to give. For example, in Priority Gas Auctions, fillers bid via the priority fees of their transactions, and the maximum tokens that will be spent by the filler are a function of the priority fee, rather than a static amount.

Problem #3: Escrow-centric interface

The interface was designed for intent protocols that escrow user funds per order as a necessary step prior to it being filled. This is not the case in intent protocols based on resource locks, also referred to as “fill-first” protocols: if the user funds are under a lock that’s trusted by the filler, there’s no need to “open” the order on the origin chain in any way before it can be safely filled.

These protocols can implement the ERC by ignoring the open function, or reusing it as a post-fill settlement function, but the result is awkward and goes against the expectations implied by the spec.

Problem #4: Gas overhead

A few design decisions have implications for gas costs. For example, the openFor function takes a struct with a lot of calldata including parameters that some implementations may not need, and the Open event includes the entire resolved order, which is another big struct that in most cases could be avoided. These are important considerations given that they impact prices for end users and that protocols often compete on gas efficiency. If the standard-compliant interface imposes unnecessary gas costs and overhead, it’s at a disadvantage against non-standard interfaces and this works against adoption.

Other Problems

A few more minor issues are:

- Chain ids and addresses don’t follow any standard. Addresses are encoded as

bytes32to support non-EVM chains, but no specifics are given about encoding non-EVM chain ids and addresses, which is likely to cause incompatibilities and integration issues. - A

fillerDataparameter infillis meant to be “provided by the filler to inform the fill or express their preferences”, but it’s abytesvalue with unspecified encoding and no mechanism to coordinate between implementations and integrators.

Proposal

Observations & Goals

Overall, the current interface may have been overfitted to a small class of intent protocols, leaving little room for others to innovate in a standard-compliant way. At the same time, basic elements common across protocols were relegated to implementation-specific extensions, weakening the case for improved interoperability. This has left the ERC in an awkward middle place.

Fixing this demands a clear understanding of the interoperability benefit the ERC aimed to bring about, which was to improve liquidity in intent protocols by lowering participation barriers for fillers.

The endgame is a maximally protocol-agnostic filler. Such a filler would be able to begin consuming orders and solving for compliant intent protocols without manual or costly integration, ideally by just adding protocol addresses to a whitelist.

We think this goal can be achieved with a standard focused on the later stages of the intent lifecycle that concerns how orders are consumed, independently of how they’re produced by users and applications. We believe the latter is a more difficult set of interfaces to standardize and that this is not required for our goal, so we’ve explicitly moved it out of ERC scope. For other projects that are looking to standardize the demand side of intents, check out OIF Contracts and OIF API Specs.

Programmable Fillers

To meaningfully improve on the status quo of non-standard protocol interfaces, a guiding principle throughout this redesign has been to look for general-purpose building blocks instead of relying on implementation-specific extensions (like the generic “order data” in the current incarnation).

A filler made of general-purpose building blocks is a programmable filler. It is able to adapt to a wide variety of intent protocols without prior knowledge of the specific steps required in each case. We can enable this by defining a common language for filler instructions and then delivering those instructions along with each order.

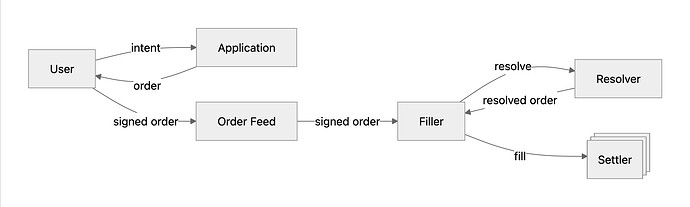

Resolvers & Payloads

Instead of transmitting orders directly in the common language, we’re preserving from the current ERC the process of resolving an order from an implementation-specific payload to a standardized data type. In fact, this is the only thing we propose to standardize: the resolver interface.

interface IOrderResolver {

function resolve(bytes calldata payload)

external view returns (ResolvedOrder memory);

}

A compliant intent protocol must implement and deploy a resolver, along with a payload format that encodes orders for that protocol. The resolver contract must validate and interpret order payloads, and produce instructions for fillers to follow.

Note that resolution happens offchain (via eth_call), even though the resolver is published onchain. This is useful because the resolver is the point of trust: filler operators whitelist resolvers, and once vetted, the instructions they produce are trusted. Vetting is done through the usual means: security audits, bounties, lindiness, etc.

Resolved Orders

The instructions for the filler are encoded in a resolved order: a representation of everything the filler must know to assess if an order is profitable and safe, and to correctly fill it and claim payment. A comprehensive spec is still in progress, but I give here the important highlights, described using TypeScript types to avoid boilerplate needed for an EVM encoding.

interface ResolvedOrder {

steps: Step[];

variables: VariableRole[];

payments: Payment[];

assumptions: Assumption[];

}

The four major elements in a resolved order are:

- Steps: Transactions the filler would have to make onchain to fill the order. For example, a call to a

fillfunction with certain calldata and sufficient allowance of some token, followed by a call to aclaimfunction. - Variables: A list of “placeholder” values that aren’t fixed in the order and will have to be determined and injected by the filler in the transactions. They may be parameters that the filler can choose, for example the address where payment should be sent, or the priority fee with which to bid in a PGA. They may also be derived values that must be computed from those parameters in a specific way, for example the amount of a token to send computed as a function of the filler’s proposed priority fee.

- Payments: Funds the filler will receive if it follows all instructions.

- Assumptions: Anything required for safety that the resolver cannot validate. This is only relevant when safety depends on certain parameters in the order, for example when an order specifies a custom cross-chain messaging protocol for settlement, the filler has to check that it trusts it, so the resolver must relay this assumption. Another example is when a fill requires a user-provided function call that must not revert, since the resolver cannot guarantee this in general the best that can be done is to check the target contract has been whitelisted.

Each step specifies the details of a transaction and also a set of attributes that are requirements such as funds, timing constraints, revert policies, etc.:

type Step = Step_Call;

interface Step_Call {

type: 'Call';

target: Account;

selector: Hex; // bytes4

arguments: Argument[];

attributes: Attribute[];

}

The calldata of the transaction is not given as a flat bytestring but as a function selector and an array of arguments. This simplifies the process of injecting variables into calldata. Each argument may be a fixed value or a variable identified by its index in the order’s variables array.

type Argument = Argument_AbiEncodedValue | Argument_Variable;

interface Argument_AbiEncodedValue {

type: 'AbiEncodedValue';

value: AbiEncodedValue;

}

interface Argument_Variable {

type: 'Variable';

varIdx: number;

}

The attributes in a step provide further detail needed to correctly perform the step, beyond the transaction data. The set of valid attributes is meant to be standardized via ERCs. We’re still defining the initial set, but here are a few examples:

type Attribute =

| Attribute_RequiredBefore

| Attribute_RequiredFillerUntil

| Attribute_SpendsERC20

| Attribute_SpendsEstimatedGas

| ... ;

RequiredBefore informs about deadlines, and RequiredFillerUntil about filler exclusivity.

interface Attribute_RequiredBefore {

type: 'RequiredBefore';

deadline: bigint;

}

interface Attribute_RequiredFillerUntil {

type: 'RequiredFillerUntil';

exclusiveFiller: Address;

deadline: bigint;

}

SpendsERC20 informs the filler that the step will spend an ERC20 token, which is both a cost that must be considered for the order PnL, as well as a prerequisite of ERC20 allowance for successful execution.

interface Attribute_SpendsERC20 {

type: 'SpendsERC20';

token: Account;

amountFormula: Formula;

spender: Account;

}

SpendsEstimatedGas informs the filler about the gas cost of executing the step in cases where simulation is not possible until later.

interface Attribute_SpendsEstimatedGas {

type: 'SpendsEstimatedGas';

amountFormula: Formula;

}

In both SpendsERC20 and SpendsEstimatedGas, amounts are given by “formulas”, which are again just a constant or a variable:

type Formula = Formula_Constant | Formula_Variable;

interface Formula_Constant {

type: 'Constant';

value: bigint;

}

interface Formula_Variable {

type: 'Variable';

varIdx: number;

}

The reason why amounts are not always constants is that they may depend on how the filler is bidding in an auction. As mentioned before, parameters that the filler must choose are represented as variables in the order, and so are any values derived from them, for example a filler’s bid would be represented as a variable, and the formula for the token amount spent in a transaction would be anoter variable that is computed from the bid.

These different kinds of variables are characterized by variable roles. Like attributes, we’re still figuring out the right set of initial roles to standardize, but the main ones are:

type VariableRole =

| VariableRole_PaymentRecipient

| VariableRole_Pricing

| VariableRole_Query

| VariableRole_Witness;

interface VariableRole_PaymentRecipient {

type: 'PaymentRecipient';

chainId: bigint;

}

interface VariableRole_Pricing {

type: 'Pricing';

}

These first two roles are ones where the filler is free to choose any value. PaymentRecipient is the simplest example where the filler is asked to inject the address where they want to receive payment funds. Pricing is a variable that will be used in other expressions to compute costs and payments. To encode the exact impact of a pricing variable on PnL, the order would define a second variable, to use as the amount formula in a SpendsERC20 attribute, with the Query role:

interface VariableRole_Query {

type: 'Query';

target: Account;

selector: Hex; // bytes4

arguments: Argument[];

blockNumber: bigint;

}

A Query variable is one whose value must be obtained via eth_call on a contract, most likely the resolver contract itself. The arguments for the call can refer to other variables including pricing variables. It is up to the filler to decide how to assign a pricing variable, but in general we expect this to be done by some black box optimization method that repeatedly performs queries until achieving a target PnL.

The final type of variable we discuss are witnesses:

interface VariableRole_Witness {

type: 'Witness';

kind: string;

data: Hex;

variables: number[];

}

This is the only place where we deviate from general-purpose building blocks. The idea is that some values may need to be obtained offchain either from a third party or built out of data that is not available on chain for the resolver. One example of this is a merkle proof of chain state, or a custom merkle proof for some protocol contract. The kind field identifies the procedure for obtaining the witness, which the filler must opt into.

Implementing a resolver as a contract in the EVM requires defining an ABI encoding of resolved orders. I will defer these details to a future article or spec, but those curious can find it in the draft specification. An example implementation of a resolver can be found here: https://github.com/slice-so/oif-contracts/blob/43c8ec5db18a9725e436b55ff4c11138fa2acad3/src/OrderResolverCompact.sol#L42

Next Steps

We’re working on a reference solver and in parallel refining the specification of resolved orders, including the exact set of attributes to include.

We’re also looking for feedback from all relevant parties: intent protocol implementers, solvers, liquidity providers, etc.