(Copied from https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/pull/3643#issuecomment-898248180)

I believe that this approach is fundamentally broken as it comingles concerns from different legal layer into one big monolithic technical blob. As an adverse side-effect, it makes basic operations like transfers significantly more expensive than a simple ERC-20 token. Furthermore, giving the issuer total control over the issued tokens does not only go against the spirit of decentralization, it might also violate investor protection laws designed to protect token holders from the issuer in case of conflicts of interest.

Here is a concrete example: let’s assume that the founder of a successful company wants to use his tokenized shares in that company as a collateral to get a credit. He won’t be able to use a DAI-style DeFi protocol as they require the ability to take exclusive control over the deposited assets that serve as collateral. So he asks his bank for a credit. The bank would love to provide the credit, but their compliance department is reluctant to approve the collateral because they know that the founder has access to the admin key, enabling the founder to “steal” the collateral at any time. I say “steal” in quotes as such an action would not legally qualify as stealing, because the taken assets still belong to the founder when used as a collateral, so it is not exactly theft. Further, the bank’s cyber insurance says they cannot provide insurance coverage for assets that are not truly under the control of the bank and the regulator is worried about the bank being able to auction off the asset in case of a default of the founder, so they do not recognize the collateral as risk-reducing when calculating capital requirements. All of this could be solved if the token offered the possibility to provide exclusive control over the token to the current holder.

As a side note, Swiss law explicitely recognizes the possibility to use crypto securities as a collateral, but it requires that it is technically ensured that the creditor has exclusive control over the crypto securities in case of a default. The reasoning behind this requirement are scenarios like the above.

So what is the correct way out?

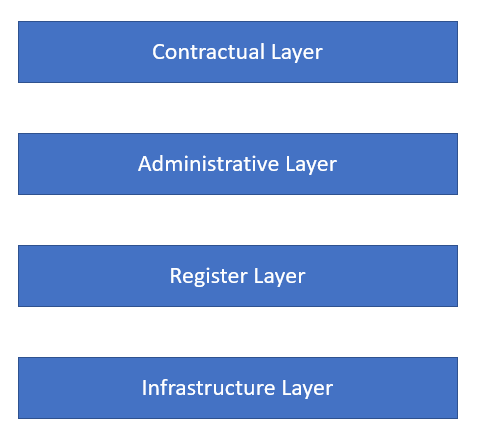

The correct way out in my opinion is to depart from the monolithic “one size fits all” approach and to go for a layered design, distinguishing four layers.

The bottommost layer is the infrastructure layer. In our case, this would be the Ethereum blockchain, fulfilling basic requirements regarding data integrity, transparency, and so on. On top of that is the register layer, which essentially is an ERC-20 token that fulfills all constitutive legal requirements to represent a security token, but none of the circumstancial compliance rules that depend on the token holder, jurisdiction, involved intermediaries, etc. Legally, compliance rules are also added on a different layer than the basic rules that define what a security actually is and what it takes to create one. Also, compliance rules come and go whereas the basic rules about the issuance and transfer of securities last for decades. It makes sense to separate these different legal concerns also in the technical implementation. So the register layer ideally is a minimal ERC-20 contract with a few features added that are strictly necessary to make the tokens legally recognized securities (under Swiss law, the only feature that is missing in the ERC-20 standard is a link to a document called the “registration agreement” that specifies what the token actually represents and other general terms the tokens are subject to). Ideally, this base contract is not upgradable at all, potentially providing the token holders with a very high level security.

On top of the register layer, there is an administrative layer that adds all kind of administrative features, for example token recovery in case of a loss of private keys. Ideally, these features are added by wrapping the token and not by extending its functionality, making sure that it is possible to free the basic token on the register layer from all administrative backdoors if necessary, for example under the circumstances described in the example. Also, having this layer separated from the register layer creates a lot of flexibility, for example implementing a different set of rules for one jurisdiction than in another jurisdiction. One should also be careful to not call this layer “compliance” layer as “compliance” is usally used in the context of financial intermediation and AML rules, which in general do not apply directly to issuers. So the administrative layer is really reserved for token administration through the issuer, not for fulfilling the compliance requirements of individual custodians or other financial intermediaries that might hold the tokens at some point in time.

The latter requirements, the compliance rules of individual intermediaries, should be implemented on the contractual layer. Often, such rules are defined in the general terms applicable to the relation between an individual token holder and a financial intermediary. Even within jurisdictions, they might differ from intermediary to intermediary, for example requiring different levels of identity verification. All these kind of requirements are implemented on top of the other layers, usually without the involvement of the issuer. Also, this layer might contain smart contracts to automatically enforce shareholder agreements and the like.

It is important to have such a separation to cleanly deal with examples like the following (again coming from Swiss law, not sure how this works in other jurisdictions): assume an employee received tokenized shares from an issuer as part of an employee participation plan. The employee is not allowed to sell the shares according to his employment agreement, but does so anyway. The company refuses to execute the transfer of the tokens, saying that the transfer would violate the employment agreement. The empoyee goes to court and the court orders the company to approve the transfer because the refusal of a share transfer requires an according clause in the articles of association, which the company is lacking. Nonetheless, the employee is liable for violating the employment agreement. This example shows that the legal situation also has different layers, with the contractual agreements on upper layers not being able to supercede the applicable terms on lower layers. Of course, the company could have implemented an additional smart contract on the contractual layer to lock the shares of the employees and to enforce compliance with the employment agreement, but it is in general not allowed to use the terms of the register layer to enforce contractual agreements that have been made on a higher layer.

Let me know if you’d like to know more. The Swiss Blockchain Federation is working on an update to their Circular on Security Tokens, outlining these concerns in more detail.