by @adietrichs and @caspar

In this document we argue for a change of the issuance curve in the upcoming network upgrade Electra.

For a more detailed account of the current issuance policy, its drawbacks as we see them, and an endgame vision for staking economics, read our writing on stake participation targeting.

Many thanks to Anders, Barnabé, Francesco, Mike, and Dom for feedback and discussion.

Reviews ≠ endorsements. This post expresses opinions of the authors, which may not be shared by reviewers.

The work presented here is based on Anders’ suggested issuance curve, linked below.

Relevant resources

- Endgame Staking Economics: A Case for Targeting

- Properties of issuance level: consensus incentives and variability across potential reward curves

- Minimum Viable Issuance

Terminology

staking ratio - fraction of ETH that is staked

SSP - staking service provider

LST - liquid staking token

tl;dr

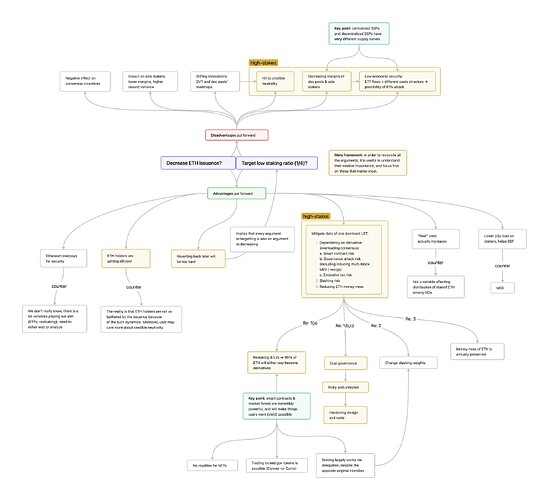

- We argue why under the current issuance policy, in the long run most ETH will plausibly be staked via LSTs.

- High staking ratios have negative externalities:

- LSTs are a winner-takes-most market due to network effects of money. This LST could replace ETH as the de facto money of Ethereum. But for true economic scalability, the money of Ethereum should be maximally trustless: raw ETH.

- Economies of scale and network effects induce more demand for LSTs as the staking ratio increases, making solo stakers relatively less competitive.

- ETH holders are diluted beyond what is necessary for security.

- We briefly introduce the endgame vision for staking economics: a stake targeting policy. However, we also highlight remaining open questions which make it not viable for Electra.

- We thus suggest adjusting the issuance curve in Electra as per Anders’ proposal. It is trivial to implement, but significantly reduces the incentive for new stake inflow and helps to mitigate many of the issues outlined above.

Why adjust the issuance policy

< This section is a shorter and less complete version of our writeup here. >

1. The current issuance policy makes it economically viable for all ETH to be staked [1]. For low stake participation, a minimum staking level is achieved by issuing very high rewards. However, those rewards do not drop off conclusively enough to ensure an upper bound to staking levels.

2. It is plausible most ETH will be staked in the long run – via LSTs. With time and adoption, the moneyness of LSTs continues to increase (more integrations and liquidity + lower governance and smart contract risk), further lowering the cost of staking due to increased economies of scale of SSPs. In short, network effects of money imply that higher adoption of some LST induces more adoption of that LST.

3. A high staking ratio is undesirable. As negative externalities outweigh benefits from increased security, the marginal utility of delegated [2] staking turns negative.

- LSTs come with added trust assumptions relative to ETH: node operator risk, governance risk, legal or smart contract risk.

- A too high issuance policy economically quasi-forces Ethereum users to expose themselves to those added LST risks.

- LSTs are a winner-takes-most market due to the network effects of money. Increased liquidity, adoption, etc., all increase the demand for a LST.

- A mass slashing of the leading SSP might not be credible and considered “too-big-to-fail”. The governance of such a dominant SSP would de facto become a part of the protocol, without being accountable to all Ethereum users.

- The winning LST could replace raw ETH as the de facto money of Ethereum. But for true economic scalability, the money of Ethereum should be maximally trustless.

- Solo stakers are relatively less competitive due to the network effects and economies of scale that LSTs benefit from.

- A too high issuance policy dilutes ETH holders beyond what is necessary for security.

- It economically constrains Ethereum users to concern themselves with the complexities of staking to prevent this dilution.

- SSPs profits, however, are proportional to amount of stake delegated with them, without suffering the dilution effects of ETH holders.

- Increased p2p networking load.

- Real staking yields plausibly higher in long run equilibrium of lower issuance policies. This would be beneficial to all stakers, but not for SSPs.

4. Our endgame vision for staking economics is a stake targeting policy, but it will take time to get there. Targeting would entail moving to an issuance curve that economically guarantees an upper bound to stake participation, mitigating all of the above concerns. However, some remaining questions and technical dependencies prevent this from being implemented in the near term. More details can be found in the FAQ section below.

We argue that leaving the issuance curve unchanged, until transitioning to a targeting policy, entails numerous disadvantages. This will become apparent as we look at hard fork timelines next.

Why in Electra?

- Changing the issuance curve requires a consensus layer hard fork.

- The current plan of upcoming hard forks (EL/CL) roughly looks like:

- Cancun/Deneb (3 weeks) - EIPs were finalized many months ago

- Prague/Electra (9-12 months) - EIPs discussed right now, final decisions soon

- Osaka/? (18-24 months) - EIPs will be decided once Pectra goes live

- Thus, Ethereum will remain under current issuance policy for at least 9-12 months, and without a change included in Electra, it will be ~2 years.

- We argue that a lack of action for two years unnecessarily risks sliding into a regime of high staking ratios. Even with the stricter limit to the deposit queue introduced by EIP-7514, that would allow for a new inflow of >40,000,000 ETH over the span of two years (max. 8 validators per epoch). This would more than double the current validator set size, with ~60% of all ETH staked. While this represents the worst case scenario, it is plausible to get close to those levels for reasons outlined above. Further, the fact that it could happen is enough cause for concern in our opinion.

- If the long term goal is to target some staking ratio, say around 1/4 of all ETH (current staking levels), then it is advisable to avoid exceeding that range significantly in the interim.

- Surpassing the stake participation target range before implementing such a policy, would necessitate a decrease in staking.

- Even with a gradual easing into the new curve, this would in practice entail a significant period, during which stakers would be insufficiently compensated until the excess stake can exit.

- Thus, we see a strong case for an adjustment of the issuance policy in Electra. In the next section, we present a proposal for such an adjustment. In our view, it satisfies two important design criteria:

- CL changes are trivial to implement, making it feasible for Electra.

- It significantly reduces the incentive for new stake inflow and helps to mitigate many of the issues outlined above.

Proposal for Electra: Issuance curve adjustment

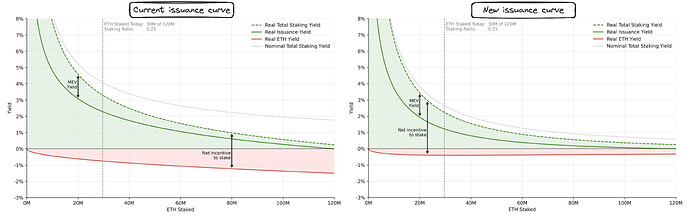

We suggest to strongly consider the adoption of a new issuance curve, as proposed by Anders, in the Electra upgrade. This change would update the issuance curve from y=cF/sqrt(D) to cF/(sqrt(D)(1+kD) [3]. Let’s consider this visually, before enumerating some properties of the new issuance curve.

^ this figure shows the current issuance curve on the left and new issuance curve on the right. The real issuance yield (green line) is the maximum amount of rewards issued by the protocol for correct validation, while accounting for dilution. Dilution (red line) is the (negative) yield of ETH holders who are diluted by the issuance of new ETH. Real total staking yield (green dotted line) is real issuance yield plus MEV yield [4]. Nominal total staking yield (grey) is the maximum amount of rewards issued by the protocol for correct validation, but not accounted for dilution unlike green dotted line. For more detail on the differences between nominal and real yields, please refer to our discussion here.

- It visibly removes many concerns around dilution for ETH holders, as dilution is capped at ~0.4% with the new issuance policy. With the current curve, on the other hand, dilution approaches ~1.5% in the limit.

- It keeps reward variability concerns for solo stakers in check and maintains correct incentives for consensus duties.

- It is trivial to implement this proposal, ensuring it will not be blocked by technical complexity or client team resources.

- The new issuance curve does not economically guarantee an upper bound for staking participation, unlike a targeting policy. However, it significantly reduces the net incentive to stake, primarily by reducing dilution.

- At current staking levels (30M ETH, or a staking ratio of 0.25), real total staking yield is reduced by ~30%.

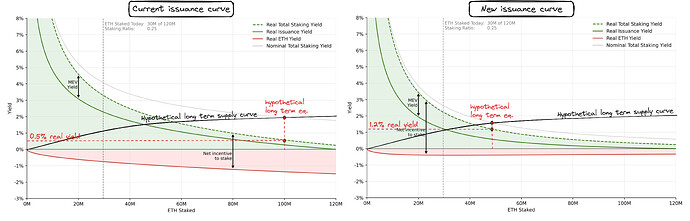

- However, lower nominal yields of new issuance curve need not imply lower real yields in the long run equilibrium. Consider the figure below, which shows higher real yields in equilibrium under the new issuance policy, given some hypothetical but plausible longer term supply curve. This would be a preferable outcome to all stakers than the hypothetical equilibrium achieved under the current issuance policy.

^ this figure is identical to the above, except for the addition of an identical hypothetical long term supply curve for both issuance curve plots. Nominal total staking yield (grey line) represents the the protocol’s demand for stake. The equilibrium level of stake is then established at the intersection between the demand and supply curve. The same hypothetical supply curve that would lead to 100M ETH or ≥ 80% of all ETH staked under the current issuance policy, would lead to less than half the amount of ETH staked under the new issuance curve. Further, we can see that real total staking yield under the current issuance policy would only be around ~0.5%, while under the new issuance curve we would obtain ~1.2% of real staking yield in equilibrium. Given this plausible example of a long term supply curve, the new issuance curve would be preferable to all stakers, due to higher real yields in the long term equilibrium, and despite exhibiting lower nominal yields.

FAQ

What level of stake participation is optimal or sufficiently secure?

- In short, current staking levels are arguably sufficiently, if not exceedingly secure.

- But ultimately there is no objectively optimal level of staking. Instead, one needs to weigh up cost of attacks (both in ETH and USD denomination) with the negative externalities of staking mentioned above.

- We point to some references, discussing what level of stake participation might be optimal or secure enough.

What about viability of solo staking?

We argue that the proposed issuance change can help keep solo staking viable. In particular, if we do nothing, a continued increase in stake participation would negatively impact solo staking viability in several ways:

- SSPs with fixed costs naturally benefit from economies of scale, allowing them to operate more profitably (or charge lower fees) as they have more ETH under management. Successful SSPs might be viewed as too-big-to-fail, reducing their perceived tail risks and further contributing to such scale effects. In contrast, solo staking comes with per-staker costs that do not decrease (rather even slightly increase with networking load!) as the total amount of stake grows. In fact, EIP-7514 was in part merged for this reason.

- As a larger share of issuance goes towards “dilution protection” and no longer contributes to real yield, stakers are left with more and more of their remaining real yield coming from MEV. This yield is by its nature highly variable, which leads to increased volatility of real total yield for solo stakers. For SSPs on the other hand this MEV income is smoothed over all validators they operate, removing staking yield volatility as a concern for them.

- The liquidity gap between solo staking and LSTs widens with increased adoption and moneyness of LSTs. Put differently, the competitive disadvantage of solo staking relative to liquid staking increases, as the staking ratio increases.

- In many jurisdictions, the basis for government taxes on staking income is the nominal income, not the real income adjusted for dilution effects. LSTs can be structured in a way to shield holders from this effect, while for solo stakers this is usually not possible. This further increases the profitability gap as the difference between nominal yield and dilution-adjusted real yield widens.

What is the tldr on the stake participation targeting policy?

We argue extensively for targeting as the endgame issuance policy here. In short:

- Today, the issuance yield does not ensure a limit to the amount that can be staked profitably. LSTs have significantly changed the cost structure of staking, making it possible that most ETH will be staked eventually.

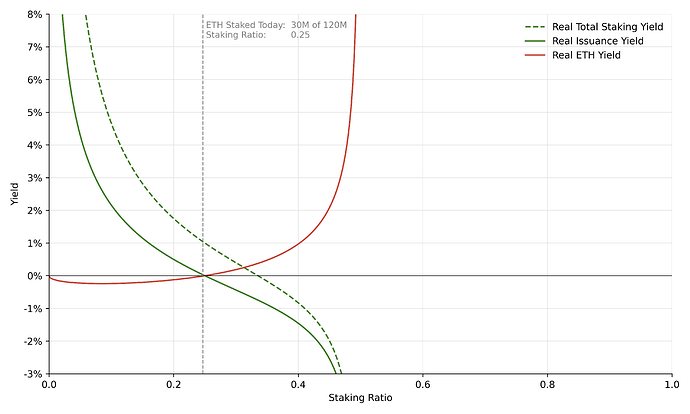

- We argue that endgame staking economics should include an issuance policy that targets a range of staking ratios instead, e.g. around 1/4 of all ETH. The intention is to be secure enough but avoid overpaying for security and thereby enabling said negative externalities.

- In particular, this approach is future-proof as it ensures sustainability with respect to the changing supply of ETH.

- The easiest mechanism for achieving targeting is an issuance curve designed to go towards negative infinity beyond some staking level, as in this figure. This practically guarantees stake participation will not grow beyond some specified range.

Why not ship targeting immediately?

- Ideally we would be in a position to propose a targeting policy for Electra already.

- However, currently there is no mechanism to capture MEV in-protocol, which means some validator staking fee logic would be required to ensure incentive compatibility of consensus duties.

- But importantly, the added complexity of a staking fee is not desirable in itself, because it would become unnecessary with future MEV capture mechanism, such as Execution Tickets or MEV Burn.

- We argue that the negative externalities of high staking levels far outweigh waiting for at least ~2 years to change the issuance curve.

- This is especially true given the proposed curve has been well studied, is trivial to implement, and in our opinion a move in the right direction, if not sufficient in the long run.

What about removing slashability of delegated stake to make LSTs more trustless?

Read more about what a more explicit separation of labor and capital could look like in Barnabé’s post on rainbow staking. But it is not in competition with our proposal, instead both could be implemented.

- While reducing trust assumptions for LSTs, it does not mitigate all concerns at all.

- Beyond slashing, LSTs still require trust assumptions: governance/legal risk and smart contract risk. Should the money of Ethereum depend on governance decisions by some liquid staking protocol, or worse, some CEX or ETF?

- Further, there are many other negative externalities such as SSP staking fees diluting ETH holders, solo stakers being relatively less competitive, increased networking load, Ethereum users having to concern themselves with the complexities of staking if unwilling to make trust assumptions, …

- To summarize, even without slashability, a LST is intermediated by some entity or protocol with certain trust assumptions and tradeoffs. Instead, raw ETH is maximally trustless.

Footnotes

[1] Modulo some ETH required for L1 txs fees…

[2] The marginal utility of solo staking also turns negative, but for much higher staking ratios. This removes all of the concerns expressed in previous section. However, if done naively it This is because many of the negative externalities are specific to delegated staking.

[3] D is the amount of ETH staked, and c≈2.6, F=64, and k=2^(-25).

[4] MEV yield is exclusively available to validators in their role as block proposers. It is calculated as the annual amount of MEV extracted (~300,000 ETH over last year) over the amount of ETH staked. As a constant amount of MEV is shared by more validators, MEV yield decreases more rapidly than issuance yield, because it does not change with staking levels. The amount of MEV has stayed remarkably constant over time. While this could clearly change, for simplicity we will refer to the demand curve as fixed.